- Reclamation

- Upper Colorado

- Programs & Activities

- New Mexico Pueblos Irrigation Infrastructure Improvement Project

New Mexico Pueblos Irrigation Infrastructure Improvement Project

Under the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009, Congress authorized $4 million to conduct a study of the irrigation infrastructure within the 18 Rio Grande pueblos, and $6 million in each of ten subsequent years to address identified infrastructure improvements. The Act required a study report to be submitted to Congress including a list of projects recommended for implementation.

Initially, detailed physical surveys of the existing irrigation infrastructure at each pueblo were completed. Most of the surveys have now been completed but remaining areas will be surveyed as specific project need arises.

The study report identified nearly $280 million in irrigation improvements, at a 2017 pricing level, needed on pueblo lands. These improvements are important to the Tribal economies, to preserving their cultural traditions for future generations, and to maximize water conservation in the Rio Grande Basin.

The report was finalized in June 2022 and submitted to Congress by the Department of the Interior's Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs. Since that time, the program has received consistent funding and projects continue to be implemented on tribal lands throughout the Rio Grande Basin. While the authorizing legislation expired in 2019, it continues to be extended annually within Reclamation's budget pending long-term reauthorization.

There is a commonly used quote within irrigation literature focused on the Southwest Region, attributed to Will Rogers and shown at right. While there is some question whether he said such, it is certainly believable; there is no doubt that irrigation is essential to productive farming in the Rio Grande Valley (Fleck, 2013).

“The Rio Grande is the only river I ever saw that needed irrigation” — Will Rogers

In the northern Rio Grande Valley, ancestral Puebloans developed a very successful culture and economy based on floodwater farming, irrigation through stream diversions, and subsistence hunting and gathering. Prehistoric Puebloans continued to improve on agricultural methods, including soil and moisture conservation methods. The earliest historical records, from the sixteenth century Spanish expeditions, noted the prevalence of agriculture within Puebloan communities throughout the Rio Grande Valley (Anschuetz, 1984; Cordell, 1984; Hammond and Rey, 1940).

By the end of the Sixteenth Century, the Pueblos intensified production through expansive irrigation infrastructure, both to increase production of native foods and to support production of European crops such as wheat (Wozniak, 1987).

Those irrigation systems continued to be utilized and improved upon in subsequent decades and centuries, by Indian irrigators as well as Hispanic and European settlers in the region. The irrigation network evolved and expanded, with numerous community-based irrigation networks that were managed by local governments or by a community-elected official. These systems were known as acequias, a term which is still used to denote community-based irrigation ditch systems (“History: The Politics of Water”, 2017).

Congress authorized the Colorado River Indian Irrigation Project in 1867, which led to the establishment of the Indian Irrigation Service under the Department of the Interior. This organization led construction and early administration of irrigation projects on Indian lands in New Mexico, and elsewhere, through the 1940’s (Wozniak, 1998).

Still, there was little overall plan, management or cooperation regarding facilities within the Rio Grande Basin until the larger scale projects were initiated beginning in the early 1900’s. In 1911, Elephant Butte Dam was completed in the lower Rio Grande Valley. El Vado Dam was completed in 1935, and the associated renovation of numerous irrigation facilities in the Middle Rio Grande Valley was finished the following year. Additional storage reservoirs, diversion dams and related irrigation construction and rehabilitation projects continued through the following decades, including construction of Cochiti Dam by 1974 (Wozniak, 1998).

Recognizing that the smaller irrigation systems did not have the same attention and support that the larger conservancy and irrigation districts had, the Water Resources Development Act of 1986 authorized the US Army Corps of Engineers to rehabilitate the acequia systems in New Mexico. Many of these systems had been in use for hundreds of years but did not have the regional organizational structures and funding for routine maintenance and prevention of deterioration. These acequias are predominantly located in North-Central New Mexico, and some extend into the systems serving Pueblo communities in the Rio Grande Basin. The USACE rehabilitated about 35 community ditches and acequia systems in New Mexico under this authority by the mid-1990’s (Wozniak, 1998).

The irrigation ditches on the Pueblo lands in the Rio Grande Basin were primarily maintained by the Pueblo farmers throughout the centuries. As previously noted, there were larger scale rehabilitation efforts undertaken with the support of the Indian Irrigation Service through the 1940’s. Since that time, irrigation infrastructure support has been provided by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Reclamation, USACE, and Natural Resources Conservation Service through various programs and authorities.

In general, however, there has not been adequate funding or programmatic authorization available to adequately rehabilitate the Pueblo irrigation infrastructure in recent decades. As a result, the Pueblo irrigation systems are predominantly and significantly aged and deteriorated. There are many systems that cannot withstand seasonal high storm flows and require extensive and labor-intensive rehabilitation annually. In addition, the Pueblo irrigation systems are plagued by inadequate baseline water flows, limited transport capacities, and high sediment loads within the water supplies (HKM Associates, 1984; Wozniak, 1998).

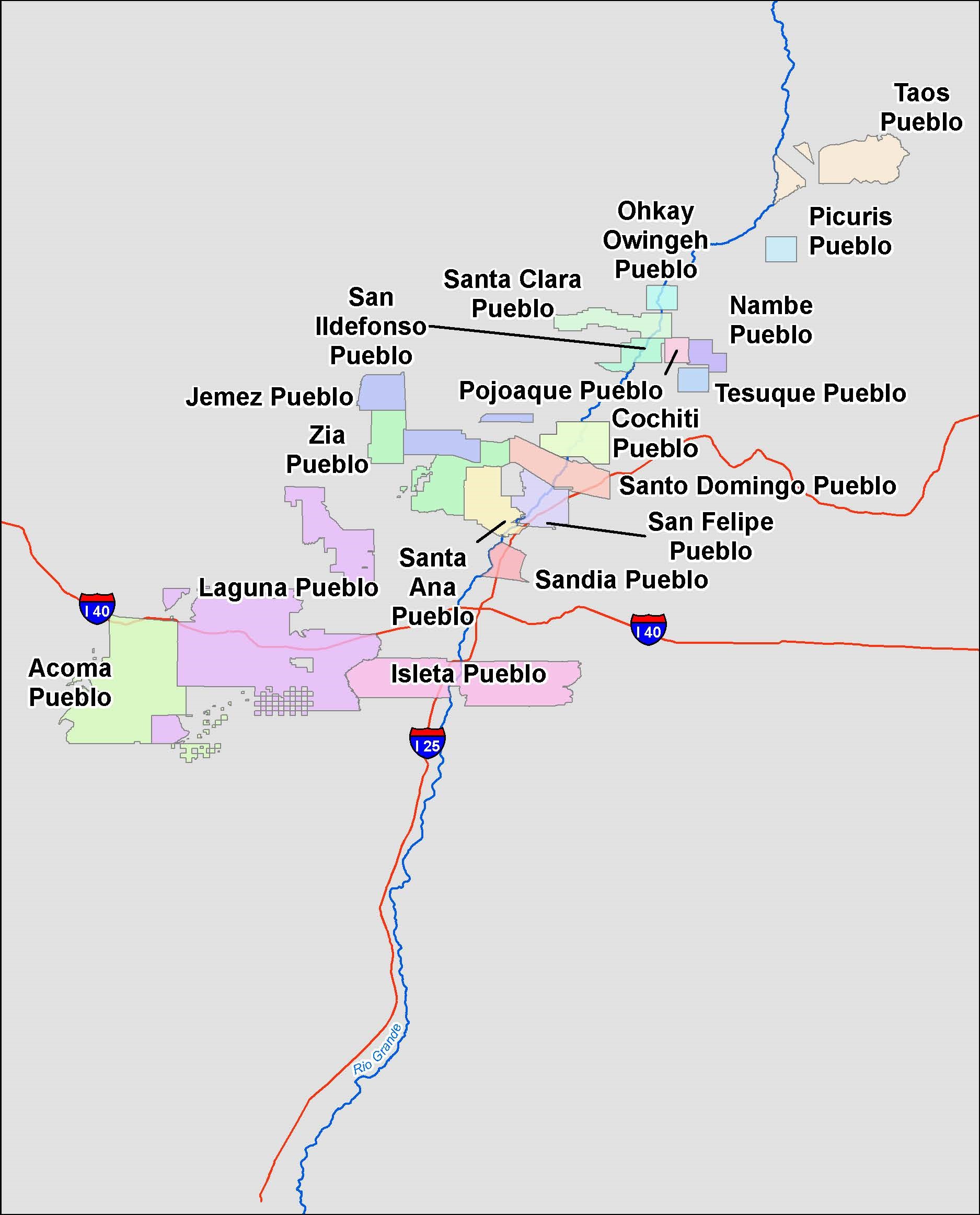

Despite these deficiencies, agriculture continues to be an integral part of the Puebloan culture and lifestyle. In New Mexico, there are nineteen Federally-recognized Pueblo tribes. Apart from the Zuni, in West-Central New Mexico and on the west side of the Continental Divide, all of these are located within the Rio Grande Basin. The eighteen New Mexico Pueblo tribes within the basin, in alphabetic order, are Acoma, Cochiti, Isleta, Jemez, Laguna, Nambé, Ohkay Owingeh, Picuris, Pojoaque, San Felipe, San Ildefonso, Sandia, Santa Ana, Santa Clara, Santo Domingo, Taos, Tesuque and Zia. The general location for each of these eighteen Pueblos is shown in Figure 1-1, Location and Vicinity Map. Within the body of this report, the Rio Grande Pueblos are discussed in general order from north to south, and from upstream to downstream within the Rio Grande Basin to the extent that makes reasonable order, given that some Pueblos are located on tributaries to the Rio Grande.

Rio Grande Pueblos

The 18 Pueblos within the Rio Grande Basin have relied on agriculture for centuries, and agriculture continues to be an integral part of the Puebloan cultural traditions and economies. However, their irrigation systems are predominantly and significantly aged and deteriorated. There are many systems that cannot withstand seasonal high storm flows and require extensive and labor-intensive rehabilitation annually. In addition, the Pueblo irrigation systems are plagued by inadequate baseline water flows, limited transport capacities, and high sediment loads within the water supplies.

Key Points

This is the initial Study required by the legislation. The development was delayed by funding constraints, and the deliverable date was subsequently extended. The goal is now to submit the report to Congress and seek support for construction funding, as fiscal year 2019 is the last year of the Authorization.

The Study identified a need for nearly $280 million in improvements to the irrigation infrastructure on Pueblo lands. Of the total, Priority 1 projects totaled nearly $133 million. In addition, there was approximately $700,000 is lower priority projects. Finally, major structure replacements were estimated at $147 million. However, further engineering review of the major structures is necessary to adequately plan and program for those projects.

The agency consultation undertaken as part of this Study has identified opportunities for cooperation among agencies that could extend the ability of each agency’s relevant Federal programs to make significant positive impacts on Pueblo lands throughout the Rio Grande Basin. A cooperative strategy between the NRCS, Corps of Engineers, and Reclamation may provide the most effective means of addressing the needs for the Pueblo’s irrigation infrastructure.

2010 Meetings with Pueblos

- November 17, 2010 held at Sandia Casino and Resort

- June 28, 2010 held at Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo

- June 11, 2010 held at the Bureau of Indian Affairs Southwest Regional Office in Albuquerque

- April 30, 2010 held at the Bureau of Indian Affairs Southwest Regional Office in Albuquerque

Meeting Information

Authorizing Legislation

In July 1998, the Secretary of the Interior hosted a national consultation with Indian tribes on Indian water rights and uses. One result of that forum was the initiation of a study to assess the condition of Pueblo Indian water delivery systems on the Rio Grande and its tributaries in New Mexico. That study affirmed the need for widespread, programmatic rehabilitation of irrigation infrastructure throughout Pueblo lands. Further, the study recommended the need for $3 million for a feasibility study, followed by an estimated $65-100 million in rehabilitation, and the potential for an additional $50-100 million in water conservation efforts (“Pueblo Irrigation Facilities Rehabilitation Report”, undated (circa 2000)).

In 2009, the United States Congress passed the Omnibus and Public Lands Act, Public Law 111-11. Included within the legislation, as Section 9106 and titled Rio Grande Pueblos, New Mexico, was the authorization to plan and implement improvements to irrigation infrastructure for the eighteen Pueblos in the Rio Grande Valley in New Mexico. The following paragraphs discuss the details of the legislation, including purpose and scope, specific requirements, grants and limitations, implementation, consultation, cost sharing, and appropriation authorizations.

The purpose of the Act was to direct the Secretary of the Interior to complete a threefold task: (1) to assess the condition of the irrigation infrastructure of the Rio Grande Pueblos; (2) to establish priorities for the rehabilitation of that irrigation infrastructure in accordance with specified criteria; and (3) to implement projects to rehabilitate and improve the irrigation infrastructure.

Applicability to the eighteen Rio Grande Pueblos within the Rio Grande Valley in New Mexico was explicit in the Act language, as well as the requirement that the individual Pueblos would be required to notify the Secretary of their consent to participate in the assessment study and development of project listings. Each of the eighteen Pueblos have provided the required consent. That documentation is included in Appendix A.

As defined in the Act, Pueblo irrigation infrastructure refers to any diversion structure, conveyance facility, or drainage facility that is in existence as of the date of enactment of the Act (March 30, 2009), and is located on lands of one of the Rio Grande Pueblos associated with the delivery of water for the irrigation of agricultural lands or for the carriage of irrigation return flows and excess water from the land served.

The specific requirements of the Act can be summarized as follows:

- Infrastructure Study: Conduct a study of Pueblo irrigation infrastructure and, based on the results of the study, develop a list of projects recommended for implementation over a ten-year period to repair, rehabilitate, or reconstruct Pueblo irrigation infrastructure (PL 111-11, Section 9106(c)(1)).

- Project Prioritization: Prioritize the project listing included within the Study based on a review of specified factors and consideration of the projected benefits of the project upon completion. Any project is considered eligible if it addresses at least one factor. The specified factors are summarized below (PL 111-11, Section 9106(c)(2)).

- The extent of disrepair of the Pueblo irrigation infrastructure, and the effect of the disrepair of that infrastructure;

- Whether, and to what extent, the repair, rehabilitation, or reconstruction of the Pueblo irrigation infrastructure would provide an opportunity to conserve water;

- The economic and cultural impacts that the Pueblo irrigation infrastructure in disrepair has on the applicable Rio Grande Pueblo; and the economic and cultural benefits that the repair, rehabilitation, or reconstruction of the Pueblo irrigation infrastructure would have on the applicable Rio Grande Pueblo;

- The opportunity to address water supply or environmental conflicts in the applicable river basin if the Pueblo irrigation infrastructure is repaired, rehabilitated, or reconstructed; and

- The overall benefits of the project to efficient water operations on the land of the applicable Rio Grande Pueblo."

- Consultation: In developing the list of projects, the Secretary is required to consult with the Director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, including the Six Middle Rio Grande Pueblos’ Designated Engineer; the Chief of the Natural Resources Conservation Service; and the Chief of Engineers (US Army Corps of Engineers). The purpose of this consultation is to evaluate the extent to which programs under these agencies’ jurisdiction may be used to assist in evaluation and implementation of Pueblo irrigation infrastructure projects (PL 111-11, Section 9106(c)(3)).

- Report: Submit a report (Study) to the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources of the Senate and the Committee on Resources of the House of Representatives that includes the list of projects recommended for implementation and any findings of the Secretary with respect to the study, the consideration of the specified factors, and the specified agency consultations (PL 111-11, Section 9106(c)(4)).

Specified Factors (Public Law 111-11, Section 9106, Paragraph (c)(2)(B)):

As described in the Act, the report mentioned above was to be completed within two years after the date of enactment of the authorizing legislation. However, that date was extended due to delays in funding appropriation. This report constitutes the first submittal in accordance with the requirements of the Act.

The Act included a provision for periodic review of the report. Specifically, every four years, the report is required to be reviewed and the project listing updated, in consultation with the Rio Grande Pueblos and as the Secretary determines to be appropriate. While authorized, Reclamation will update the report every four years or as specified in potential future reauthorization legislation.

Subject to appropriation, the Act authorizes the Secretary to provide grants or enter into contracts with the Pueblos to plan, design, construct or otherwise implement projects to repair, rehabilitate, reconstruct or replace Pueblo irrigation infrastructure. There are limitations imposed on any assistance. Projects that are not deemed eligible include on-farm improvements, and repair, rehabilitation, or reconstruction of any major impoundment structure.

When planning for the implementation of any specific project, the legislation requires consultation with, and approval from, the applicable Pueblo; consultation with the Director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA); and coordination, as appropriate, with work conducted under the BIA’s irrigation operations and maintenance program.

The cost sharing provisions of the legislation specify a Federal share of no more than 75 percent, with the stipulation that the Secretary has the discretion to waive or limit the required non-Federal share if the Rio Grande Pueblo demonstrates financial hardship. The non-Federal share may also be satisfied by in-kind contributions, including the contributions of valuable assets or services. Further, any potential State contributions can also be utilized as non-Federal share.

In addition, for projects within the Six Middle Rio Grande Pueblos (Cochiti, Isleta, San Felipe, Sandia, Santa Ana, and Santo Domingo), the Secretary may accept a partial or total contribution from the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District toward the non-Federal share. The MRGCD, or District, is a political subdivision of the State of New Mexico that was established in 1923 and is further discussed in the following chapter.

The Act authorized up to $4 million to conduct the Study, and up to $6 million for each fiscal year 2010 through 2019. Through fiscal year 2018, nearly $3 million has been appropriated. The Study, including field surveys, has utilized these funds. In addition, supplemental funding was provided by other Reclamation programs, including Native American Affairs, Drought Relief, and support from the Albuquerque Area Office.

Contact

Thank you for your interest in this project. For further information, please contact:

Albuquerque Area Office Public Affairs

555 Broadway NE, Suite 100

Albuquerque, NM 87102-2352

(505) 462 - 3576

smnelson@usbr.gov